“No one must look at the rocks of the bridge. People knew that some day it would fall. They must not anger the Spirit Chief by looking at it, their wise men told them.

‘Bridge of the Gods’ ca. 1929, photographer unknown.

Read more here

“No one must look at the rocks of the bridge. People knew that some day it would fall. They must not anger the Spirit Chief by looking at it, their wise men told them.

‘Bridge of the Gods’ ca. 1929, photographer unknown.

Read more here

Written by: James D. Keyser, Indian rock art of the Columbia Plateau

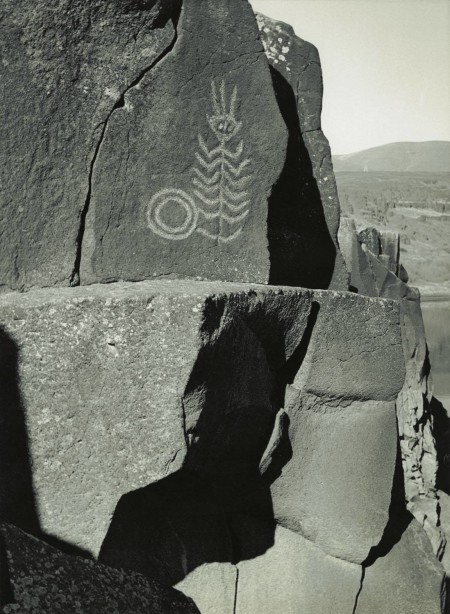

Rock art is one of the most common types of archaeological site in Oregon, occurring from the Portland Basin to Hell’s Canyon and the high desert canyons along the Owyhee River to far southwestern Oregon’s Rogue River drainage. Including both pictographs (paintings) and petroglyphs (carvings), the rock art at these sites was created as early as 7,000 years ago until as recently as the late 1800s. Although petroforms—a third type of rock art composed of outlines cut in desert pavement or boulders laid out in the form of animals or humans—are found elsewhere in North America, none has been discovered in Oregon.

Including both pictographs (paintings) and petroglyphs (carvings), the rock art at these sites was created as early as 7,000 years ago until as recently as the late 1800s. Although petroforms—a third type of rock art composed of outlines cut in desert pavement or boulders laid out in the form of animals or humans—are found elsewhere in North America, none has been discovered in Oregon.

Archaeologists have classified Oregon’s rock art into five traditions, that is, spatially broad-based artistic expressions that were created during a defined period of time. The traditions generally follow Oregon’s aboriginal ethnic/cultural boundaries. Thus, the Columbia Plateau Tradition reflects the art of Sahaptian-speaking tribes such as the Tenino, Nez Perce, Umatilla, and Klamath-Modoc, while the Great Basin Tradition comprises the art of the Numic-speaking bands of the Northern Paiute. In the river valleys of western Oregon, the few sites that are known represent the Columbia Plateau Tradition and a little-known California rock art expression called the Far Western Pit and Groove Tradition, which is the product of Tututni and Kalapuya artists and probably members of other tribes as well.

Cover to book text is from.

The subject matter of rock art in the Columbia Plateau Tradition is primarily humans, animals, and geometric designs, one of the most common of which is tally marks—a horizontally oriented series of three to more than thirty short, vertical, evenly spaced, finger-painted lines. Despite its limited subject matter, Columbia Plateau art functioned in several ways, including as a commemoration of the acquisition of spirit power during a vision quest and as a shaman’s ritual expression of power.

Yakima Polychrome designs and the closely related imagery of the Columbia River Conventionalized Style of the Northwest Coast Tradition served in healing and mortuary rituals and were used to witness mythic beings and places. Some images of animals and hunters in the Columbia Plateau Tradition were painted and carved as hunting magic. In the Klamath Basin, art in the Columbia Plateau Tradition has several stylistic expressions, but current research suggests that all of them were the exclusive purview of shamans.

Columbia River Gorge

Far Western Pit and Groove Tradition rock art is found from the southern Willamette Valley near Eugene into the Umpqua and Rogue River drainages, where it occurs as cupules—shallow dimples—and simple geometric forms pecked and ground into streamside boulders. Known as Baby Rocks or Rain Rocks, ethnographic sources indicate that these simple petroglyphs were carved both by shamans accessing and using supernatural power to call the salmon and communicate with the gods and by women who wanted to bear a child.

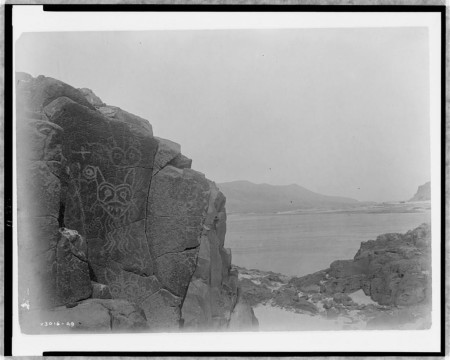

Vantage, WA.

Certainly much Great Basin rock art was made by shamans who were acquiring or using supernatural power, and much of the geometric imagery may have been generated in the artists’ minds by stimuli experienced during a trance. Other Great Basin imagery, however, is likely to have been made in conjunction with subsistence activities during the seasonal round of these high-desert hunter-gatherers and likely had a broader function as part of the rituals associated with subsistence.

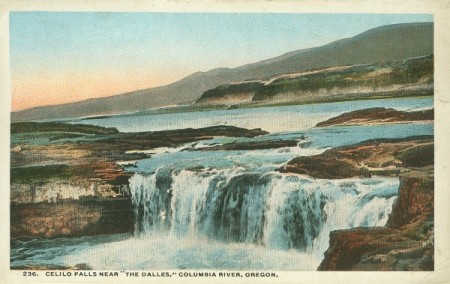

Celilo – Wyam 2005 Salmon Feast

Loss of Wyam caused pervasive sadness, even in celebratory events. The old Longhouse is gone. The Wyam, or Celilo Falls, are gone. Still courage, wisdom, strength and belief bring us together each season to speak to all directions the ancient words. There is no physical Celilo, but we have our mothers, fathers, sisters, brothers, and our children bound together for all possible life in the future. We are salmon (Waykanash). We are deer (Winat). We are roots (Xnit). We are berries (Tmanit). We are water (Chuush). We are the animation of the Creator’s wisdom in Worship song (Waashat Walptaikash).

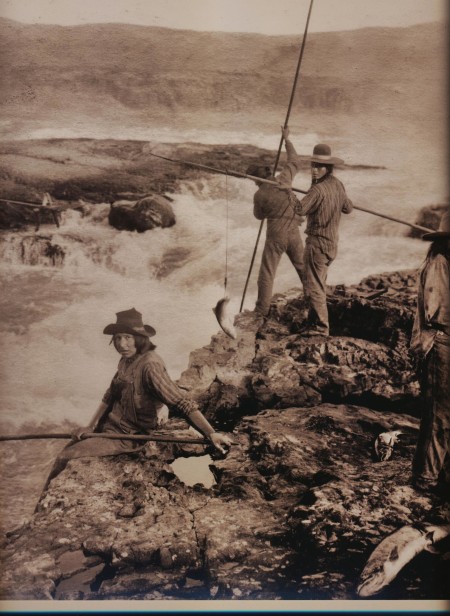

Unknown fishermen, unknown year, unknown photographer.. any information would be appreciated.

The leader speaks in the ancient language’s manner. He speaks to all in Ichiskiin. He says, “We are following our ancestors. We respect the same Creator and the same religion, each in turn of their generation, and conduct the same service and dance to honor our relatives, the roots, and the salmon. The Creator at the beginning of time gave us instruction and the wisdom to live the best life. The Creator made man and woman with independent minds. We must choose to live by the law, as all the others, salmon, trees, water, air, all live by it. We must use all the power of our minds and hearts to bring the salmon back. Our earth needs our commitment. That is our teachings. We are each powerful and necessary.”

published in River of Memory: The Everlasting Columbia,Layman,WilliamD.,Ed. UP: WA. Seattle, WA 2006

“…. They didn’t sign away their rainy Eden or sell it, die in warfare, or move to reservations, not until twenty-five years after the catastrophes that swept most of them away. It wasn’t smallpox that laid them low. Suddenly most of them were simply gone. The Wapato Lowlands in particular were empty and silent. Did

God call them home? The few survivors walked away dazed. Took to speaking other languages. Were replaced by strangers. After a few decades hardly anyone remembered that they had ever been there.”

God call them home? The few survivors walked away dazed. Took to speaking other languages. Were replaced by strangers. After a few decades hardly anyone remembered that they had ever been there.”

Read more of “She Who Watches — Tsagaglalal By Rick Rubin” here: http://www.ochcom.org/chinook/

Listen to the story, ‘She Who Watches — Tsagaglalal’, as told by Ed Edmo:

“I am now old. it was before I saw the sun that my ancestors discovered the Wah’-tee -tas, the little ancient people who wore robes woven from rabbit’s hair. They dwelt in the cliff. My people saw a little short fellow, like a person.

Alfred A. Monner (1953), warns of a dangerous whirlpool in the eastern Columbia River Gorge.

- Tokiaken Twi-wash (Yakama) told L.V. McWhorter this story in 1912

A grand spectacle! The sheer magnitude of these living waters, pummeling in their forever song of change.

Post Card, Near The Dalles, 1917

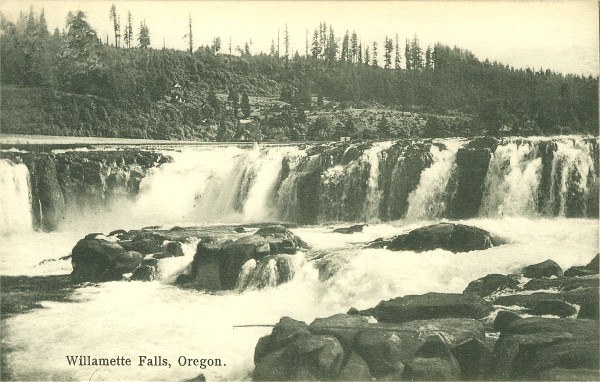

Coyote came to a place near Oregon City and found the people there very hungry. The river was full of salmon, but they had no way to spear them in the deep water. Coyote decided he would build a big waterfall, so that the salmon would come to the surface for spearing. Then he would build a fish trap there too. First he tried at the mouth of Pudding River, but it was no good, and all he made was a gravel bar there. So he went on down the river to Rock Island, and it was better, but after making the rapids there he gave up again and went farther down still. Where the Willamette Falls are now, he found just the right place, and he made the Falls high and wide. All the Indians came and began to fish. Now Coyote made his magic fish trap. He made it so it would speak, and say Noseepsk! when it was full. Because he was pretty hungry, Coyote decided to try it first himself. He set the trap by the Falls, and then ran back up the shore to prepare to make a cooking fire. But he had only begun when the trap called out, “Noseepsk!”

All the Indians came and began to fish. Now Coyote made his magic fish trap. He made it so it would speak, and say Noseepsk! when it was full. Because he was pretty hungry, Coyote decided to try it first himself. He set the trap by the Falls, and then ran back up the shore to prepare to make a cooking fire. But he had only begun when the trap called out, “Noseepsk!”

He hurried back; indeed the trap was full of salmon. Running back with them, he started his fire again, but again the fish trap cried “Noseepsk! Noseepsk!” He went again and found the trap full of salmon. Again he ran to the shore with them; again he had hardly gotten to his fire when the trap called out, “Noseepsk! Noseepsk!” It happened again, and again; the fifth time Coyote became angry and said to the trap, “What, can’t you wait with your fish catching until I’ve built a fire?” The trap was very offended by Coyote’s impatience and stopped working right then. So after that the people had to spear their salmon as best they could.

A Creation Story

“Long, long ago, when old Man South Wind was traveling North, he met an Old Woman, who was a giant.

“Will you give me some food?” asked South Wind. “I am very hungry.”

“I have no food,” answered the giantress, “but here is a net. You can catch some fish for yourself if you wish.”

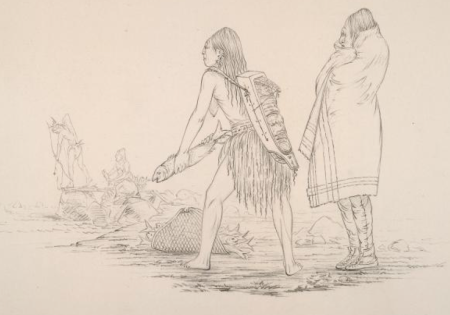

George Catlin. 1850

But the old giantress cried out, “Do not cut it with a knife, and do not cut it crossways. Take a sharp knife and split it down the back.”

But South Wind did not take to heart what the old woman was saying. He cut the fish crossways and began to take off some blubber. He was startled to see the fish change into a huge bird. It was so big that when it flew into the air, it hid the sun, and the noise of its wings shook the earth. It was Thunderbird.

Thunderbird flew to the north and lit on the top of Saddleback Mountain, near the mouth of the Columbia River. There it laid a nest full of eggs. The old

Saddle Mountain, Oregon

The old giantress broke some other eggs and then threw them down the mountainside. They too became Indians. Each of Thunderbird’s eggs became an Indian.

When Thunderbird came back and found its eggs gone. it went to South Wind. Together they tried to find the old giantess, to get revenge on her. but they never found her, although they traveled north together every year.

That is how the Chinook were created. And that is why Indians never cut the first salmon across the back. They know that if they should cut the fish the wrong way, the salmon would cease to run.

Always even to this day, they slit the first salmon down the back, lengthwise….

My heart lives here, amongst the rivers and restless winds. The hills and snowy peaks, wild flower and ancient tree. My bones rest here, in stone, and mud, and stories yet told.

Family at Celilo, 189?

“My generation is now the door to memory. That is why I am remembering.” Joy Harjo

Many of us River People speak about still hearing those waters fall. Like a longing at the doors of our dreams. Or a remembering that we know in the beating of our hearts. Each pump a drum of longing to be home, amongst the joyful jumping of Salmon. A familiar smoke drifting from shacks holding old stories. The repeating patterns of metaphor, and the sound of Echoes of Water Against Rocks.

Watch the documentary, Echoes of Water Against Rocks, here:

The first thing I saw was Crow. It was almost as if I was looking through a camera, and Crow put his face right up to the lens. He put his eyeball up to the lens, and then his beak, then his whole face, and then he vanished.

The next thing I saw was an enormous, gorgeous, perfect rose, free floating in mid-air. It was very dark pink, almost red, and then it became a lush, deep, dark red. It had petals like a peony, but it was a rose. The rose became larger and larger, and as it grew, it opened to reveal a velvety center of infinite petals.

I was on the edge of a forest. Eagle appeared, in a fierce emanation. I got onto his back.

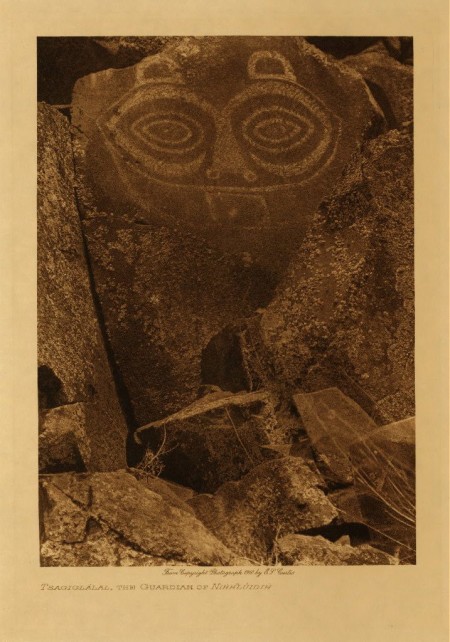

Thunderbird Petroglyph, Horse thief lake, OR.

First, she pulled out a wonderful medicine blanket that she made for as a gift. It was very long, and when she unfurled it, the length of it tumbled over the cliff for many yards. As she began to gather it back up into a neat roll, she smiled lovingly. She had spent many moons making this blanket, and each stitch contained a prayer. This blanket had very powerful protective medicine. She placed the rolled-up medicine blanket into the saddlebag on the Eagle. Then she handed me a magic compass. The compass was made entirely of quartz crystal. She showed me precisely how to use it for navigation. The face of the compass was completely blank, empty of all markings. It had a clear crystal face, with a quartz crystal needle. The compass would guide us on our journey. Finally, she handed me a key, carved out of jade. I placed the key in my medicine pouch. Crow Dancer danced around and flapped his wings and stomped his feet and made a blessing for the journey, and we were off again.

First, she pulled out a wonderful medicine blanket that she made for as a gift. It was very long, and when she unfurled it, the length of it tumbled over the cliff for many yards. As she began to gather it back up into a neat roll, she smiled lovingly. She had spent many moons making this blanket, and each stitch contained a prayer. This blanket had very powerful protective medicine. She placed the rolled-up medicine blanket into the saddlebag on the Eagle. Then she handed me a magic compass. The compass was made entirely of quartz crystal. She showed me precisely how to use it for navigation. The face of the compass was completely blank, empty of all markings. It had a clear crystal face, with a quartz crystal needle. The compass would guide us on our journey. Finally, she handed me a key, carved out of jade. I placed the key in my medicine pouch. Crow Dancer danced around and flapped his wings and stomped his feet and made a blessing for the journey, and we were off again.

Paul Kane painting of Loowit (Mt. St. Helens), which was a symbol of rebirth to the Cowlitz People.

The cave was guarded by a blue dragon. The phoenix approached the dragon and requested permission to enter the cave. The dragon asked the phoenix what business he had in the cave, and the phoenix replied that he had come to “get his boy.” The dragon gave him three challenges. He challenged him to a game of chinese checkers. The phoenix won. He challenged him to a fire breathing contest. The phoenix won. And finally, he asked the phoenix to guess his name. The phoenix went up to the dragon and whispered something in the dragon’s ear. The dragon looked at him, utterly astonished, and granted entry. The dragon breathed fire up into the ceiling above the entry of the cave, and a trap door opened. We all went in. We found ourselves in a very narrow, tight tunnel. It was so narrow and tight that we barely had room to move. The only way was for us to make ourselves smaller and to keep moving, otherwise we would get stuck. I couldn’t see a thing. There were so many twists and turns that it made me dizzy. I remembered the magic compass. As soon as I pulled it out of my medicine pouch, the needle on the compass began to glow and pulse. The needle quivered for a moment and then pointed very strongly in a particular direction, which we followed. After that we were fine. We just followed the glowing compass needle through the labyrinthine tunnels and eventually came out into a part of the cave that had a large central clearing. There were several openings and cave mouths all along the perimeter. However, the compass showed us precisely where to go. We followed it’s guidance to one particular little cave entrance, with its door locked up tight. I took out the jade key and placed it in the lock. It fit perfectly, and with one turn of the key, the door flew open and there we found a little boy. He was curled up in a corner, lying on his left side, with his arms around his knees, huddled up against the cold, wet corner of the cave. He had his face to the corner of the cave and his back to us, and even though he heard us come in, it took a long time for him to stir.

Crow teachers. Public domain photo

He looked to be around seven years old. He had long dark hair, and he looked terribly sad. His eyes were large and melancholy and he would not make eye contact. Crow went up to him to try to make eye contact. Then he hopped up onto the boy’s left shoulder and told him that we were here to take him home, if he would like to come with us. The boy just sat there as if he hadn’t heard a word. Crow asked the boy if he liked it there, in the cave. The boy shook his head slowly. “No, not really.” said the boy. “Would you like to come home?” asked Crow. “I don’t know.” Crow explained to the boy that things were different now, and that he would be safe. He told the boy that he had been missed and that he was loved, and that he would be welcomed back home with open arms. The boy indicated that he would like to come with us. I reached into the saddlebag for the medicine blanket, and wrapped it around the boy. He knew who had made it. I didn’t have to say a word. Now, when I looked at his face, he looked older, closer to maybe eleven years old or so. After this, his face would change, and his features would become those of a younger boy, then an older boy. But he was always somewhere between seven and eleven years old.

Crow stayed on his left shoulder. Phoenix stepped forward so the boy could climb onto his back. I followed with Eagle and we quickly exited the dank cave. As we left, Phoenix dropped a colorful tail feather, as an offering to Dragon, and Dragon picked it up and waved. We shot back up through the ocean, just as we had shot down, and we found ourselves back at the cliff. Grandmother Rose was there. Crow Dancer was there. Grandmother Rose embraced the boy for a long time. She pulled him onto her lap and rocked him and kissed him and hummed to him. She pulled the medicine blanket snugly around him and sighed. Crow Dancer placed a breastplate of porcupine quills on the boy and gave him his elk skin robe. Grandmother Rose took the boy’s long hair and divided it into three sections. She made three braids, and then braided those three braids into a single braid. She talked about the power of three, that three was the number to keep in mind. Crow Dancer placed three big shiny black crow feathers in the boy’s hair. Phoenix placed more feathers in the boy’s hair, magnificent feathers of brilliant hues; red, orange, yellow, violet, blue, green…He gave the boy a walking stick on which was carved: “NOW IS THE MOMENT OF POWER.” Grandmother Rose told the boy that it was important to forget the past, and to not worry about the future. “Life is short,” she said. “All we have is this moment.” Spider made an appearance and wove a cloak of scintillating light around the boy. It sparkled and shined with a pure radiance. She said that all he ever needed to do, if he ever got scared, was to ask Spider for a cloak of light, and she would weave something up for him. He will always have access to protection. All he has to do is ask.

Mesa near Taos, NM.

H a v e n © 2016

There were embraces and acknowledgements and blessings, and then it was time to say goodbye. We climbed down a ladder made of rainbow light and came to an open, grassy field. It was just outside the same edge of forest from which our journey had begun. Many animals began to appear and quickly disappear; Raccoon, Red Tailed Hawk, Bighorn Sheep, Unicorn, Coyote. As we landed on the grassy field, we joined a fire ceremony that was being held in the boy’s honor. The boy stood at the fire, wearing a white mask. Raccoon came up to him and took off the boy’s mask and tossed it into the fire, where it was consumed. There was another mask underneath. Again, Raccoon took off the mask and tossed it into the fire. This went on and on, mask after mask. The first masks were completely opaque, but as they continued to be peeled away they became more transparent. I could see through the final mask, and I saw that the boy was weeping. Raccoon stood there and looked at the boy with great compassion. Raccoon was not going to take off the final mask. The boy wept for a long time at the fire. Finally, he reached up and slowly removed the final mask, and placed it quietly into the flames. The boy’s face softened and he stopped crying. Everyone laughed and cheered and came over and embraced the boy. He was glad to be home.